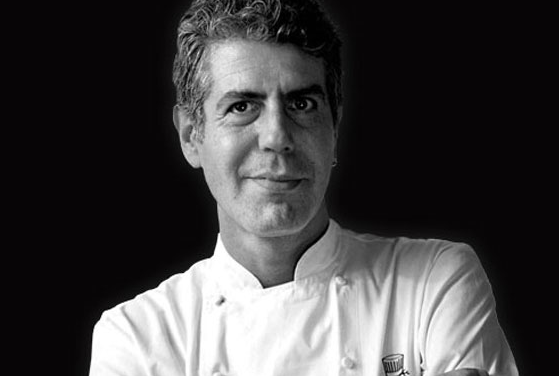

Pablo Miller, far right, with his Fincruit staff. Photo: Fincruit

Phoebe Hopson speaks to British-Colombian entrepreneur Pablo Miller, who is ahead of the curve, and determined make shock waves with his innovative company Fincruit.

Some would call it crazy, quitting a job with a six figure salary to come and start a recruitment company in Bogotá, even more so if you know no one and have never lived there. However, this it is exactly what Pablo Miller did last January. While still being very much in the start-up phase, Fincruit, a recruitment company aimed at disruptive technology, already turns over on average £20,000 to £40,000 a month, sourcing talent for multinational companies like Besedo and Genius Sports in Latin America, Europe and the US.

“I’m not afraid of a blank piece of paper,” says Miller oozing entrepreneurial confidence. However, this isn’t his first venture and, although only 25, Miller is certainly not a newbie to the recruitment business. During his first year at university in the UK studying politics and sociology, he founded his first Fintech recruitment company from his bedroom. “Before coming to university I spent some time in a small agency, there I learnt that all you need is a laptop and a phone,” he explains candidly. “Like most British-Colombian families, we spent a lot of time sending money back, I remember getting the bus with my mum to Western Union and it taking ages. Then all these Fintech companies started to pop up, offering clever ways of send money. This caught my attention so at university I thought, why not give it a go?” By placing a £30 advert on Gum Tree and boldly ringing up companies, Miller landed his first hire. “I got £3,700 for my first hire, I had never seen so much money in my life,” he says with pride.

Financial technology, broadly known as ‘Fintech’ describes the innovation in the financial services industry over the last 15 years. Examples of this movement are BillGuard, an application that enables users to scan credit and debit cards alerting possible frauds or Transferwise, a peer-to-peer money transfer service far cheaper than using banks or Western Union. Over the last few years, Bogotá has seen a rise in international Fintech companies like Uber and the start of homegrown ones like PayU Latam.

“People are starting to invest in Colombia and we want to be there from the beginning,” explains Pablo. However, the plan for his company, Fincruit, goes beyond wanting to be the early bird. “If I just wanted money I’d sit in a room and do this, but what I want is a Fincruit company in Bogotá that will build game-changing businesses in Europe, and eventually help them come to Latin America, ultimately we are helping the image of Colombia.”

This fearless attitude and foresight is the driving force behind Miller’s success – both in the UK and in starting his business in Colombia. However, despite receiving £100,000 in financial support from the former vice-chair of UBS Investment Bank, he was quickly faced with the realities of being an entrepreneur in Colombia and the legal pains of going it alone. “In London it takes a few days to register a company, here it’s a tedious 15, 20 steps. I set my company up without even properly researching the accountancy law,” he confesses.

In fact, red tape and the banking system here have been a continuous thorn in his side during Fincruit’s first year. Stringent measures against money laundering make international transfers weighty in paperwork. “They say an international transfer should take three days, but last time it took much longer.” These cash flow difficulties take the foot off the gas at Fincruit and dampen their desire to grow and change. Nevertheless, Miller is mindful of how Colombia’s tricky past has generated a strong lack of trust, particularly in banking. “The problem with Colombia is that the compliance department needs to know why you’re being sent the money and where they got it from. You need a letter and six months’ bank statements, that shows where their source of income comes from.”

Another challenging issue is the need for connections. “I also find Bogotá very elitist,” says Miller. Indeed, good recommendations go a long way in Colombia, a good word from a friend can speed you past bureaucracy and earn you trust with the banks.

I want to break this barrier that if you don’t come from a well recommended family you can’t do business in this country.

However, Miller doesn’t view these difficulties as insurmountable, in fact he believes, heartwarmingly, it is something that entrepreneurs like himself can change. “I want to break this barrier that if you don’t come from a well recommended family you can’t do business in this country, that’s what my goal is, if you have entrepreneurial spirit and you’re willing to take risks, I think you will have a lot of what you see in the UK, like the Alan Sugars or James Caans.”

James Caan, venture capital, real estate royalty and Dragon Den’s judge is actually an important player in Miller’s story. “He was my hero, I read his book The Real Deal, and implemented it, I even used to imitate the way he spoke.” In 2011, Caan put up a post looking for the next recruitment entrepreneur in the UK. At this point Miller was already active in a space provided by Nottingham University with his company Russell-Miller Partners. He describes them as full of passion but making “continuous fuck ups.” A well crafted email from this happy-go-lucky bunch landed them a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to pitch to James Caan.

Unsurprisingly, their university-style presentation was torn to shreds. “They thought we were hilarious,” chuckles Miller, “there were people with 20-30 years of experience and we were just kids.” However, their efforts were not in vain and with a little persistence, Caan offered Russell-Miller Partners a £50,000 investment. “He saw we were fearless. If we could make money without structure, then what could we do with his help?”

The investment put Pablo “into fifth gear.” And at just 21, by this point a university dropout, he became the first out of 3,000 consultants to turn over £80,000 in one month. Despite this remarkable success, a year into the company, Miller became dissatisfied with the old-school Wolf of Wall Street sales tactics. “We had to hit our KPIs but there was no regard for quality,” he explains, “I became a yes-man, a people-pleaser. I fell out of love with the business, because it wasn’t the business I wanted, I didn’t want a business all about making cash, where you don’t build a brand or create value for your clients.”

After a painful separation, Pablo decided to trust in his capabilities and go it alone, deciding to take a holiday to his maternal Colombia. “From what my family had told me, I had the impression that the city was a war zone with people walking around with donkeys.” He tells the story of his naivety with a good dose of self-mockery. “I was initially scared, but then a trip walking round the 93, made me think, what the hell is going on here? I felt something special and it caught my interest.”

He’s since set up office not far from Parque 93 and – another example of his willingness to break the mould – he says he’s hired “No one normal”. He has attracted a talented and mixed bunch. “We have a business graduate Spaniard, a mathematician Korean-Paisa, and a Brit who has worked in commercial banking.” And he explains, they are there because they believe in what the company is doing: “Everyone who works for Fincruit could leave the company now and get a higher paid job in a more stable environment, but we all believe in this Latin American market.”

Ever the canny businessman, he takes the opportunity to let me know that he’s hiring – contact him through their website if you’re interested.

The Fincruit team are not afraid to branch out as they build their future. Already the company has moved away from pure recruitment as they move towards consultancy. They are providing the complete package by helping companies move to Bogotá, finding them talent and aiming to keep employees fulfilled.