Oliver Pritchard takes a light-hearted linguistic trip around the accents of the British Isles – beware, stereotypes abound

Oliver Pritchard takes a light-hearted linguistic trip around the accents of the British Isles – beware, stereotypes abound

Well, term is over and I’m turning my attention to a more playful idea: how to speak like a native, with a native accent. Of course, if it were that easy, everyone would simply learn just like that, but here are some tips and tricks that might help you to sound like you come from the UK, or to help you understand your Celtic friends.

English is a difficult language to control. Spanish is (technically, at least) controlled and regulated by the Real Academia Española, a group of fat old European men who dictate how everyone should use ‘their’ language. English, by contrast, is often worryingly vague. At higher levels, students sometimes ask me what is correct. The answer is often “we don’t know”. English permits changes based on things like common usage, and exceptions have often become rules in their own right. Hundreds of books have been written on the rules of English, as if such a thing existed.

The sheer diversity of countries that use the language has led to some interesting developments, some of which we’ll take a look at today! Note that much of this is meant to be light-hearted and fun, for those of you that might be going on vacations or holidays rather than serious commentary.

English RP (see below) or American Standard Pronunciation are often considered the best pronunciation methods, although to be honest neither would come anywhere close to my favourites (West Indian; Indian; Geordie; lowland Scottish; Dubliner; New Yawk, if you’re interested) as both are terribly dull.

British English

Obviously the language developed in Britain, although as usual, there’s some confusion between England and Britain – not to mention the UK. The UK as a whole has a surprisingly wide variation of accents, and many people will claim that they can accurately identify accents from parts of even quite small cities. For example, I can fairly confidently spot differences between around four or five different parts of my home city Bristol, despite it only having a population of 400,000. The founder of this newspaper and I don’t use anything like the deep Brissol accents of the South or the Bristle accents of the East. Bristolians stretch everything out into long vowels and have a habit of changing syntax and grammar agreements, as well as frequently ending sentences with prepositions. “I is looking for Arron, tell him to give I a call if you know where he’s to.”

Oop North

I am aware that a certain “Game of Thrones” is mystifyingly popular all around the world, and that they all talk like Northerners. The single most distinctive pronunciation issue is the long /a:/ which Northerners almost never use, preferring to rhyme bath with cat rather than car. Also, the troublesome ‘ight’ for non native speakers is often pronounced as /i:/.

Oop North in England, certain archaic forms have been preserved, so you’ll hear things like yon or ‘ee. Although these have been lost in standard English as the language has changed, they remain in the Northern dialects. This is also true of owt and nowt. Most strikingly, there is a common use of over-contraction, where the third person ‘s’ is often lost in the contraction along with everything else, and famously, that ‘the’ is often contracted to t’: “there’s trouble oop at t’mill”. Finally, it’s very common to drop the plural ‘s’. “The beer is five pound”, not five pounds.

Most of this focuses on Yorkshire, the heartland of t’North, but there are some variations, over t’wrong side of t’Pennines in Lancashire and the far north in Newcastle. Famously, Tino Asprilla struggled to make himself understood up there. It is, however, quite probably the single most fun accent in the entirety of English. First, almost all vowels are long, regardless of how they ‘should’ be pronounced.

Then, almost all the vowel sounds should start deep in the throat and sound full rather than sharp. Finally, the sentence stress should usually be slightly more exaggerated than in other forms of English.

People in the Midlands have an accent, but it is so famously boring that I fell asleep every time I tried to do some research.

Scotchland

Scotland has a particularly hard to understand dialect in terms of pronunciation. You shouldn’t find the lowlands too hard to understand, but Glasgow and the highlands can be genuinely hard to follow. Vowels are often stretched oot longer than usual, /l/ is often not pronounced and /r/ is almost always rrrolled. Scottish English also has a very wide range of specific vocabulary and you might be interested to know, that like Spanish, there is a diminutive form -ie. In terms of grammar, the Scots use the continuous forms more than other varieties of English, which some more arrogant English speakers consider to be ‘wrong’.

Wales

Perhaps Britain’s most melodic accent can be found in the singsong intonation of the Welsh, who sound like they’re reciting poetry all the time. Welsh English isn’t a dialect particularly rich in idioms or vocabulary, but there are two interesting grammatical features. Firstly, Welsh speakers commonly use the question tag “isn’t it” regardless of the form of the sentence, and secondly, they often place auxiliary verbs (commonly ‘to be’ and ‘do’) at the end of sentences for emphasis: “Very happy with these empanadas, I am”, “I really love guaro, I do”.

Cockernees and Estuary

Now we move to London, a cold brutal city which is reflected in its various accents. Most of them are harsh and sharp, so although there’s actually quite a variety throughout the capital, it comes out something like Laaandan. Think of cockney sellout Johnny Rotten singing with the Sex Pistols.

The English generally are famous for swallowing sounds, and in London this goes to the extreme. /th/ is often simplified to /f/ and /t/ almost doesn’t exist unless it’s at the start of a word, in which case it’s spat out violently. All sounds take their hard equivalent or are simply dropped. For example, nothing becomes nuffink.

Grammatically, Londoners love the question tag isn’t it to be shortened further to “innit” and used in basically all sentences. The possessive my is replaced simply with me; “it’s me phone, innit?”. Double negatives are absolutely normal. “I didn’t do nothing, mate!”

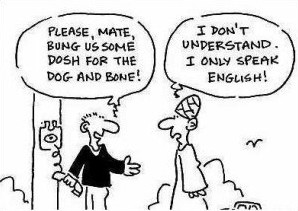

The greatest sign of London (specifically Cockney) speech is the use of rhyming slang. This was originally used to fool the police, but is now a relatively common part of speech. Classic examples include “apples and pears” for stairs, “whistle (and toot)” for suit and “boat race” for face. New examples occasionally emerge, such as “you having a giraffe” for laugh and “Britney Spears” for beers.

What is popularly thought of as ‘English English’, or ‘correct English’, is what we call Received Pronunciation, or RP. This is the English you will find on the BBC, hence its alternative name of BBC English. It’s actually considered unusually posh in Britain – some call it the Queen’s English – and most people would assume you’re doing something special if you’re using it. It’s certainly not a normal way to speak, other than in very rich circles. Although it’s often considered the ‘best’ way to speak, trying to use RP will make you sound strange. Perhaps the best example of a good RP accent can be found in the work of Sir David Attenborough, the world famous biologist. Try repeating “the rain in Spain falls mainly on the plane” (the Estuary equivalent is “the water in Majorca don’t taste like what it oughta”) to practise a good RP accent.

What is popularly thought of as ‘English English’, or ‘correct English’, is what we call Received Pronunciation, or RP. This is the English you will find on the BBC, hence its alternative name of BBC English. It’s actually considered unusually posh in Britain – some call it the Queen’s English – and most people would assume you’re doing something special if you’re using it. It’s certainly not a normal way to speak, other than in very rich circles. Although it’s often considered the ‘best’ way to speak, trying to use RP will make you sound strange. Perhaps the best example of a good RP accent can be found in the work of Sir David Attenborough, the world famous biologist. Try repeating “the rain in Spain falls mainly on the plane” (the Estuary equivalent is “the water in Majorca don’t taste like what it oughta”) to practise a good RP accent.

British English in general, and particularly English English, has a habit of being excessively polite. It’s not at all unusual to thank someone five or six times in a simple exchange such as buying a newspaper, as well as an equal number of pleases. Famously, British people will often apologise as a default communication method, even when not at fault. It’s considered odd to be direct, especially with strangers, and English people will often go out of their way to avoid giving personal information or opinions, leading to endless boring conversations about the weather.

Another instance of this can be found in the way English people phrase requests, where modals become much more common. “What I would like you to do, if it’s not too much trouble, is that do you think you could open the window, if that’s OK, don’t want to cause any difficulty”. This can often cause confusion with foreigners, who assume that all those modals actually have some sort of proper meaning.

Well, there it is! Whether you want to talk like the Queen, Mary Poppins or Sean Bean, hopefully this will help you a bit, or just provide a bit of a laugh. It’s also worth pointing out that although we can’t publish them in a family newspaper, not all English English is so polite, and there exists an enormous book of euphemisms and swearwords known as Roger’s Profanisaurus. Look it up!

This is the first in a series of articles about the different Englishes that are spoken around the world. Now you have a taste of the UK accents, watch out for future editions where we will delve deeper into the diverse uses of this international language.

If you have any comments or suggestions, get in touch with us at [email protected] or leave a comment below.