Every night before lights out in the dorm of his prestigious colegio in Zipaquirá, a teacher would sit and read to Gabriel García Márquez and his classmates, introducing the boys to the classics of world literature. The first of these authors, Gabo would later recall, was Mark Twain.

It’s “an appropriate recollection,” writes Márquez’s biographer Gerald Martin, “for a man destined to be – among other things – the Mark Twain of his own land.”

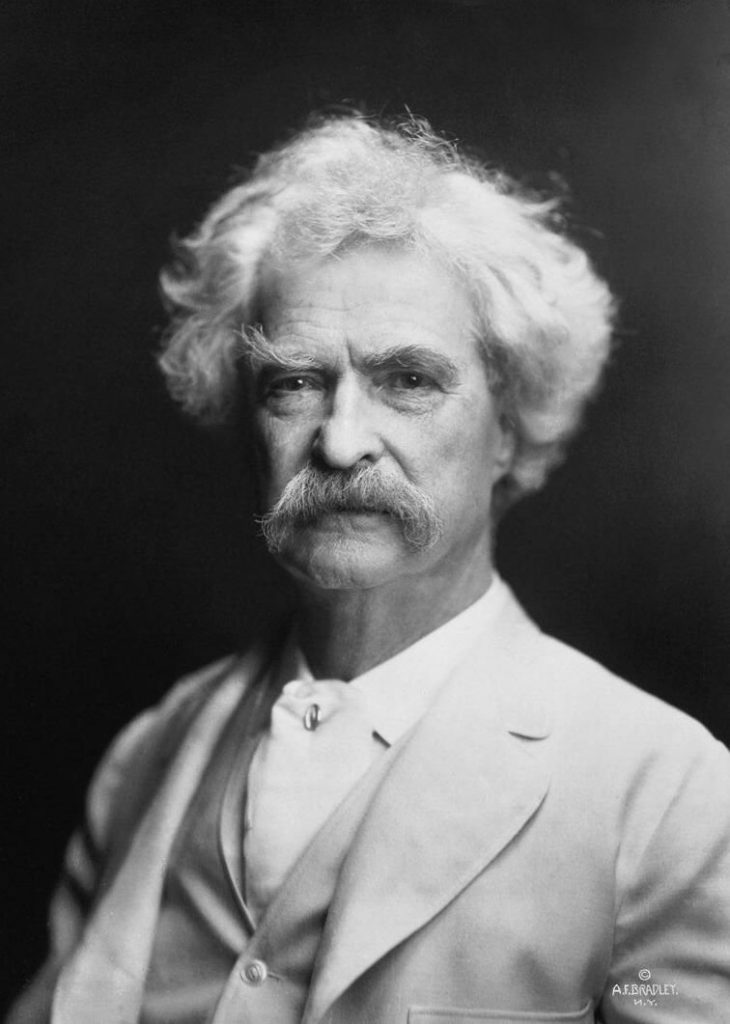

Today those lucky enough to know his writing celebrate the 182nd birthday of Samuel Clemens, aka Mark Twain, a giant of American literature whose influence on United States art, culture, and national identity cannot easily be overstated.

As Martin points out, Twain was and is, like Márquez, “a symbol of the country, definer of a national sense of humour and chronicler of the relation between the provincial realm and the centre.”

Indeed, if Gabo’s writing somehow communicates what it is to be Colombian, Twain’s work articulated something collectively recognized (by many) as “American.” Twain constructed a distinctively American protagonist with a distinctively American voice. He was, according to William Faulkner, “the first truly American writer.” “All modern American literature,” remarked Ernest Hemingway, “comes from one book by Mark Twain called Huckleberry Finn.”

A humorist, storyteller, and social critic, Twain was a masterful satirist with an uncanny ability to express the profound with an irreverent wit. His works channeled the dialects of the antebellum American South while also internalizing the moral dilemmas of the young nation – and his true genius lay in his ability to seemingly keep things lighthearted while simultaneously grappling with social injustices and hypocrisies of his time.

His life and writing

Mark Twain grew up in a small town in Missouri, along the iconic Mississippi River – a waterway from which Twain drew inspiration in much the same way Márquez’s writings were inspired by the Magdalena. Also, like Gabo, Twain first gained fame working as a journalist.

In 1876, he published perhaps his most popular novel, The Adventures of Tom Sawyer. The novel is an idyllic portrayal of boyhood along the Mississippi River, full of playing hooky, fist fights, boyhood crushes, and the other adventures of its protagonist, Tom Sawyer, alongside his buddy Huck Finn.

Likely his most widely read novel, Tom Sawyer was even paid homage to this year in Colombia, at Medellín’s Fiesta del Libro y la Cultura (Book and Cultrual Festival). As the 10th installment in the festival’s ‘little yellow book’ series, the story of Tom Sawyer was reimagined and retold à la Paisa. Tom Sóyer Mucho Culicagao, written by Koleia Bungard, follows the shenanigans of Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn’s Paisa counterparts as the two wander the streets of Aranjuez, causing mischief, having adventures, and of course drinking Pony Malta and eating papas rellenas.

Despite Tom Sawyer’s popularity, it’s that book’s sequel, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, published in 1884, that is considered by most to be Twain’s masterpiece.

As the title implies, the novel follows the boyhood adventures of Huck Finn – but the work’s undertones are much darker. For all its humor and escapades, it’s the troubling depiction of racism and moral hypocrisy underlying the novel’s playfulness that sticks with (and haunts) the attentive reader.

The book offers a portrait of the antebellum South filtered through the uneducated, rebellious, and ‘uncivilized’ boy narrator’s perspective. As Huck ‘naively’ reasons through contemporary norms and rules, he’s unable to make sense of his community’s nonsensical moralities. Exposing the self-serving nature of these norms, Huck enacts a powerful rejection of predominant cultural values.

Huck and Twain’s legacy

More than 130 years later, Huckleberry Finn remains one of the most celebrated American novels ever, a masterwork by one of the father’s of American literature. Even so, it is infamous as well as famous.

While considered by most critics to be a scathing critique of slavery, certain individuals and groups throughout the 20th century have argued that the book itself is racist. Citing, among other things, its use of the N-word, these groups have even moved to have the book banned (sometimes successfully).

Whatever the case, the indelible mark left by the novel and its author on American culture and identity is undeniable. And, if nothing else, the controversy surrounding the book is a testament to the deeply rooted moral tensions still troubling the American psyche.

With the United States – and much of the world, for that matter – facing an especially worrisome moment, and perhaps doing a bit more soul-searching these days, returning to the classics of artists like Gabo and Twain can be an invaluable exercise in sorting through a complex moment in history.

As the incredibly quotable Mark Twain once remarked, “The man who does not read good books has no advantage over the man who can’t read them.”