Journalist and writer Juan Miguel Alvarez (left) speaking at the Medellin Book Fair in September. Photo by Arjun Harindranath

Conflict journalist Juan Miguel Alvarez, winner of the Simón Bolivar Award in 2017, recently spoke with The Bogotá Post about the role of independent journalism in the country after the peace agreement, the violence against social leaders and the building of historical memory within Colombian society.

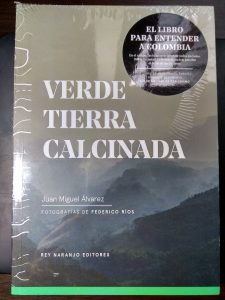

Alvarez presented his new book Verde Tierra Calcinada ( which translates to “Scorched Green Earth”) at the Medellín Book Fair. A compilation of seven chronicles about seven isolated regions of the country, the book traverses regions considered by him as outside the “bubble” in which most Colombians live in. This bubble represents one of the most important barriers for the construction of a single and joint national project for Colombians.

Are the cycles of violence being repeated in the Colombian countryside?

I think the current violence is much lower than we’ve had in other periods in Colombia’s history and it would be more manageable if the state were stronger. The problem with violence in Colombia is that the state is too weak, and I don’t mean only the government, I mean also other social institutions like the academy, civil society and the press. So as we are a weak society, the violence has always overcome us.

Colombia is living at a strategically important moment; a moment that the country has already lived in twice. In 1953, when 3450 members of the liberal guerillas demobilized and the country lived a mayor drop in the murder and general violence rates, but the country couldn’t take advantage of the situation because the anti-communist radicalism remained outside of the agreements and ended up committing a series of murders that triggered the armed resistance of the FARC and other guerrillas. The leftist groups had the perfect excuse; the existence of the reactionary violence of the establishment must be faced with the violent resistance of the masses.

The second similar moment was between 1989 and 1993, when the M-19, EPL and Quintin Lame guerrillas surrendered their arms, another propitious moment (for peace) but the country was living the parallel phenomenon of drug dealing. The State and the society again couldn’t take advantage of the momentum as they allowed for the anti-communist forces to commit violence against the members of the Patriotic Union party (leftist party composed by leftist social leaders and ex guerrilla members).

Colombia hasn’t been able to take advantage of those quieter times, those few moments of stillness that had been achieved, because it didn’t control the reactionaries who were inside their own establishment and that creates an excuse for radical leftist groups to operate and to keep renovating.

So we are currently in a really similar period: we demobilized the paramilitary groups, we demobilized the FARC, the ELN is still operating although is very small, but the problem is that there are many signs of reactionary violence all around the country, a violence that is not anti-communist anymore but anti-cooperativism, anti-agrarian, etc. So this violence may end up triggering–if we don’t control it–a repeated scenario that is worse. This reactionary violence is real. It has killed many social leaders, it has threatened many people and it has falsely accused many thinkers and journalists. As I said, if we don’t neutralize this far-right violence it’s very possible that a leftist reactionary violence will develop underneath.

“The state has to control their own reactionary violence to save peace”

Who within the central government has an interest in keeping social leaders, thinkers and journalists quiet?

There has always been reactionary positions within the state, in both the army and the political elites. Firstly, army generals who have been mostly trained at the United States Army School of the Americas (USARSA) the most prominent anti-communist military academy of the world. They are reactionaries by ideological training.

The state’s violence promoted by some politicians has always found people within the army to carry out that violence. Therefore, if the army doesn’t move away from the ideological training of the School of the Americas–this counterinsurgency doctrine developed in the sixties by the CIA–we are not going anywhere, because the far-right will always have someone who does the dirty job and that’s the worst kind of paramilitarism because it isn’t civil but official, made by someone within the state, how do we fight that?

Also, as long as the national economy is dependent on hydrocarbons and the financial markets (banks, stock, bonds), which are both managed by the central authorities, there will always be a political establishment that will do everything to keep control of the economy and, from that point of view, will do everything to dominate the regions. Therefore, if we want to think about a better country, we have to think about a different economy.

“The violence is more manageable than ever, but Colombian society as a whole is still fragile”

Has anyone tried to ban the stories or articles that you write?

To be honest, no one is interested in the kind of journalism that we do. The impact that we can generate in the political arena is minimum. So the political establishment isn’t interested at all, even if I write 200 books related to criminality in some region, or denounce threats to the life of some social leader, nothing happens.

Alfredo Molano (one of Colombia’s most important conflict journalist and writer) wrote many books denouncing what happens in the regions and nothing ever happens. This book (Verde Tierra Calcinada) only caught the attention of people who have been directly affected by violence, the establishment hasn’t done anything to stop me, Alfredo Molano or any other journalist or writer, because it doesn’t affect them. Nevertheless, even if they would like to shut us up, in the current times there are so many ways to share our stories (facebook, twitter, radio) that the only thing they could do is kill us.

Although not so interested in journalists, this establishment that has the political power, led by the quasi-criminal Centro Democrático party, is very concerned about the historic memory that is being built, because the Comisión de la Verdad (Truth Commission) is going to determinate legally who-did-what in the conflict, and many people who were hiding their crimes will be exposed. For example, the military who have yet to be caught with anything.

Some weeks ago there was a scandal when the Comisión de la Verdad asked the army to let them check the proceeding documents of some military operations conducted some years ago where they could see the details of everything: who shot, who ordered the shootings, how many weapons and bullets, if there was air support, etc.

When the commission started to collate the different versions of the army, victims, guerrillas and paramilitary groups, many of the people that had committed crimes weren’t judged and were, in several cases, still controlling what happens with the violence in the country and will continue to have more accusations against them.

When the commission started to collate the different versions of the army, victims, guerrillas and paramilitary groups, many of the people that had committed crimes weren’t judged and were, in several cases, still controlling what happens with the violence in the country and will continue to have more accusations against them.

This is what worries them, not journalism. They will try to control the commission, either trough laws, intimidation, false allegations or physical violence. The question is if the official historical account remains unscathed as it is right now: the bad guys were the FARC and the paramilitaries and the good guys were the military.

After the peace agreement, do you have more freedom to travel around the country and to tell more stories?

Undoubtedly, both the FARC and the paramilitary groups controlled big portions of Colombian territory. If you were visiting, for instance, Calamar (located in Guaviare department) in 2005, there was a big risk of being murdered by the paramilitaries or entering the Arquía river region between Antioquia and Chocó four years ago was impossible.

I visited two weeks ago and there was no presence of illegal armed groups anymore, the atmosphere is calmer and people are willing to talk about their problems, which wasn’t possible before. The only remaining problem are the areas with illegal coca plantations, where journalists and visitors have to be more cautious, but that is a small portion of territory.

Verde Tierra Calcinada by Juan Miguel Alvarez (with photos by Federico Rios) is available in Spanish now through Rey Naranjo Editores.