Warning: This article contains graphic images of severe tungiasis, a potentially deadly parasitic condition that leaves deep ulcers in the skin. Although the story does have a happy ending, the pictures may gross you out if you’re reading this while eating your porridge.

Back in 2002, at the height of a dengue outbreak in northeastern Brazil, a German specialist in tropical diseases named Hermann Feldmeier was brought in by government officials to determine the dimensions of the epidemic. A stranger in a strange land, the German doctor quickly found himself an audience as a group of children followed his every move as he surveyed the favelas of Fortaleza, Brazil.

The children moved unusually, the doctor remembered, and at closer inspection he could see that their toes were inflamed, misshapen and bent at awkward angles that explained their limping movements. The soles of their feet were also ulcerated with deep lesions like nothing he’d seen before.

“What do you have?” Feldmeier asked one of the children in Portuguese.

“Bicho de pé”, came the answer, translating literally to ‘bug-of-the-foot’.

“Is it common here?”, Feldmeier asked.

“Todo mundo tem”, one of the children said.

Everybody has it.

Under the skin

Feldmeier realised on returning to Germany that, to his astonishment, what he’d found in Brazil was largely uncharted territory in the literature on tropical diseases. With the exception of a single observation by a Swiss naturalist in 1943, almost nothing was known about tungiasis, the crippling condition that afflicts mostly children and the elderly by hosting the parasite known as tunga penetrans.

“Tungiasis is probably the most neglected of the tropical diseases,” Feldmeier said, speaking to The Bogotá Post from his office at the Charité Campus in Berlin.

Tunga penetrans is commonly referred to as the sand-flea but also goes by the names chigger, jigger or chigoe flea. In addition to South America, the parasite can be found in the Caribbean, sub-Saharan Africa and Madagascar. Its gruesome way of life, however, is the same all over the world.

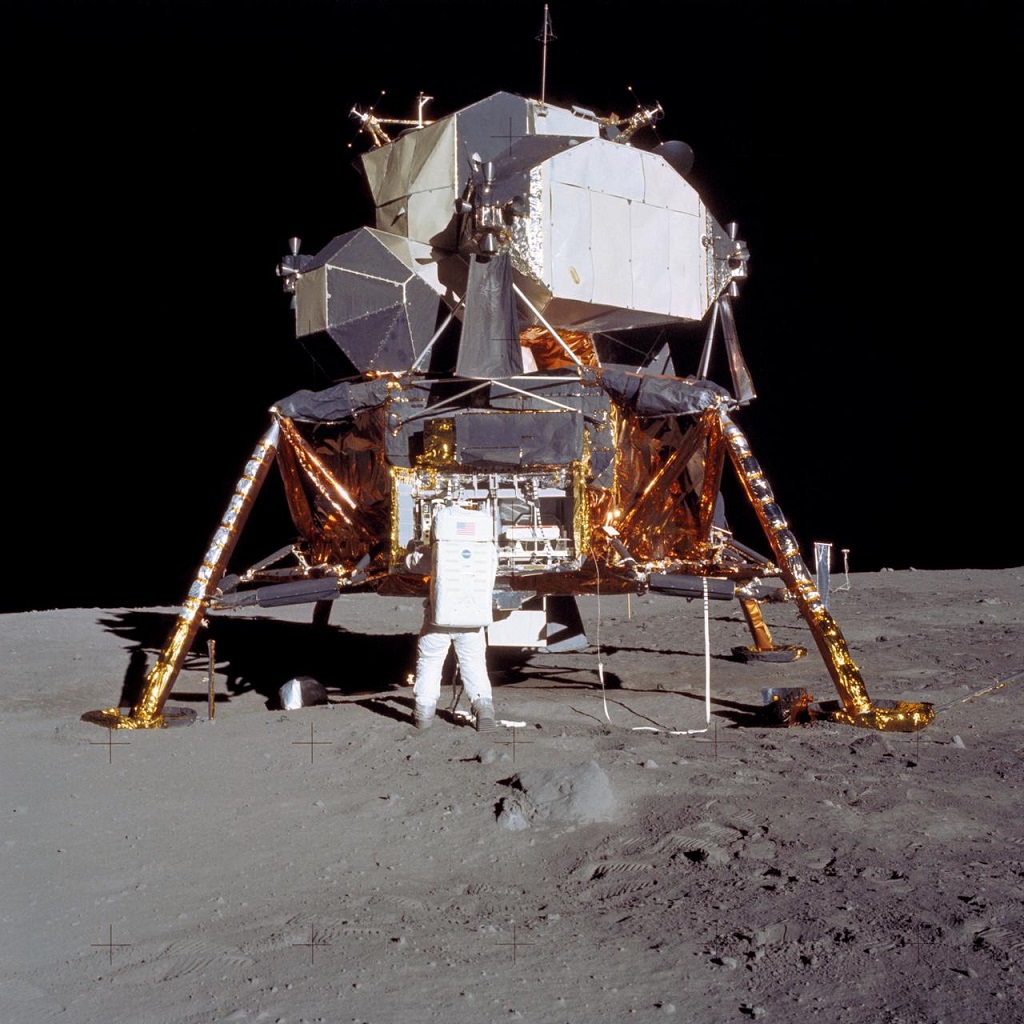

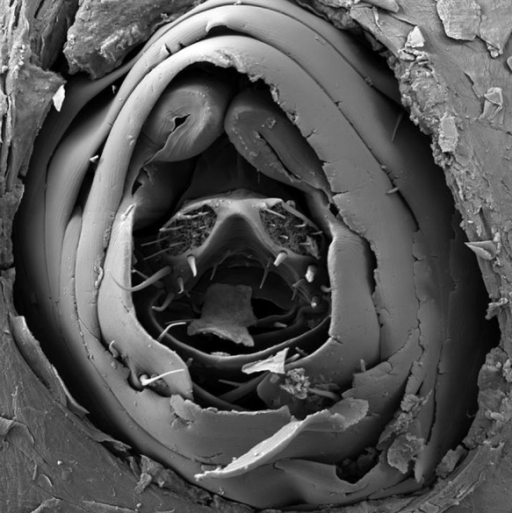

Scanning electron migrograph of an embedded female sand-flea. The parasite takes in oxygen and lays eggs from the orifice pictured above. Image courtesy of Tropical Medicine and Health.

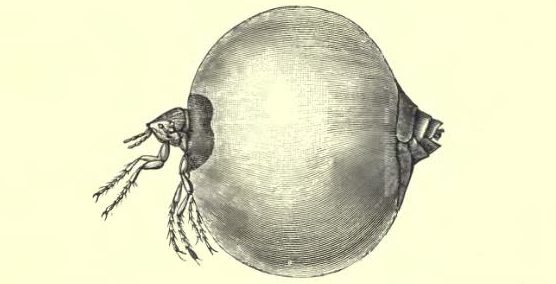

The major culprits in the world of sand-fleas–known as la nigua in Colombia–are the female of the species. Attaching themselves to humans, the female sand-fleas burrow into the epidermis just under the surface of the skin.

Despite being microscopic in size, they then begin to feed on nutrients under the skin to the point where they expand up to 2000 times its original size in 10 days. Growing like a tumour the sand-flea can grow “to the size of a pea”. The nutrients allow them to lay eggs, which are deposited via an orifice (see photo above) that protrudes from the surface of the skin. They breath in oxygen from the same orifice and, after their eggs are laid, the sand-flea deflates and dies.

If they land on soil or sand, the eggs hatch and complete their life-cycle within the earth until the next unsuspecting host walks on them. In humans, sand-fleas usually embed into the soles of feet though in theory they can burrow into any part of the body that makes contact with the earth.

In a recent study of severe cases of tungiasis in the Colombian Amazon, Feldmeier and his co-authors found patients within indigenous communities with sand-fleas embedded in their ankles, knees, elbows, hands, fingers and around the anus. The ulcers caused are also often coupled with infections that can, if left untreated, be life-threatening.

Deep in the Amazon

The 72-year-old woman was from Wacará, in the department of Vaupés, and was of Cacua heritage. Accompanied by her nephew, she found it so painful to walk that she had to be carried in a hammock by two men to the boat that guided them down the river for six hours to the local hospital in Mitú.

Her body was slowly wasting away when Feldmeier first saw her and it became clear that she was eating very little in her condition. Much like the children of the favela in Fortaleza, clusters of ulcers appeared across her feet, resembling the eyes and skin of a pineapple (see photo below). As the woman didn’t speak Spanish, her story was relayed through an interpreter.

“Some of the patients were so sick they had more than 1000 parasites penetrated into their skin. They were almost dying” Feldmeier said. There also appeared to be few remedies available to the communities outside of individually prying the parasites out with a sharp instrument.

The German doctor had been in Mitú at the time and asked his colleagues for the old woman, along with four other members of indigenous communities along the Río Vaupés, to be brought into the only hospital in the region. He had seen very few cases of this severity and, along with his coauthors, sought to find the factors that lead to such a severe case of tungiasis. The answer wasn’t entirely to do with the parasite alone.

A cluster of embedded sand fleas in a patient’s foot. We warned you the pictures would be gross. Image courtesy of PLOS Negected Tropical Diseases

How the patients are treated and treatment for the patients

All of the patients that Feldmeier saw had one other commonality beyond the tungiasis: they were all desperately poor. The 72-year-old woman, for example, had one son who could not care for her and could only provide her one meal a day. Given that she had already suffered orthopaedic problems with her knees, she was resigned to her hammock the whole day.

Her grandson too was largely abandoned and suffered from learning and cognitive disabilities. Playing on the earthen floor next to her, he also developed severe tungiasis. When he was brought into the hospital, the 16-year-old boy weighed 23kg.

Contact with the ground where there can be organic material or ash from the fire led to a healthy environment for the parasite to breed in numbers. “The life cycle takes place in the hut,” Feldmeier said, “You get out of your hammock and place your feet on the ground and the next generation of parasites penetrate into your skin.”

But in addition to this, the fact that the patients were largely abandoned and unable to access quality healthcare were significant factors in contributing to their severe tungiasis. Feldmeier said that the indigenous saw it as a curse and that the patients were treated like lepers and people were unwilling to help. “There was no help from the community. This is a paradigmatical setting where tungiasis can develop into a life-threatening condition.”

This situation wasn’t unique to South America either. In Kenya, previous treatments of tungiasis involved applying potassium permanganate to the foot and the compound would stain the patient’s foot purple, stigmatising them to their community even further.

It was in this context that Feldmeier came upon a newer chemical treatment by the use of dimeticone oil. He had seen natural remedies–like that of a mixture of coconut oil and Indian Neem tree leaf extract–be of moderate success in Africa but it was the trials of a silicone oil called dimeticone that showed the most promise in treating tungiasis by blocking the parasites’ oxygen supply.

So far, the results have been astonishing. “Just need drops of the oil where the parasite has penetrated the skin. Its efficacy is in the order of 98-100%.”

Happily, in the case of the indigenous patients in the photos above, two treatments of the dimeticone oil led to their full recovery. It is hoped that the wider spread of such treatments can lead less deaths in the developing world from the scourge of tungiasis.