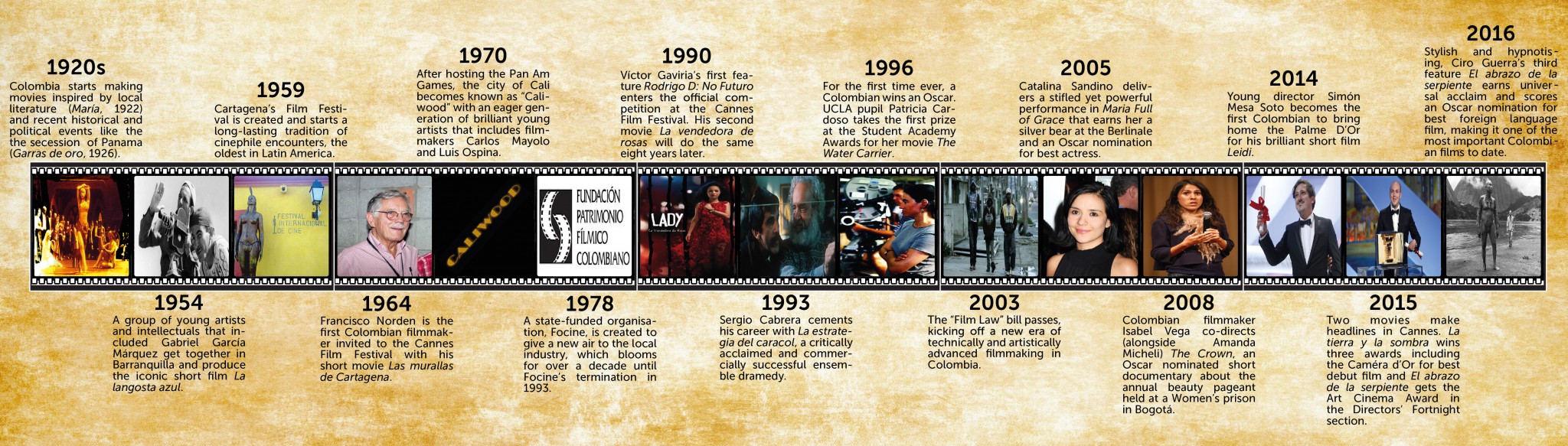

- A timeline of highlights from the Colombian movie industry – Milestones of Colombian cinema

- With the recent successes at the box office we take a look at The state of Colombian cinema

- An interview with El abrazo de la serpiente’s art director – ‘In the jungle everything has spikes’

- Some of the best picks from the Winners of the Best Foreign Language Film category

Milestones of Colombian cinema

Director César Acevedo receives the Caméra d’Or prize at the Cannes Film Festival from American actor John C. Reilly for his film La tierra y la sombra.

The state of Colombian cinema

The country’s Oscar nomination brings the national film industry into the spotlight. Carolina Morales looks at its current state, the challenges it faces and what the future may hold

The media hype generated by El abrazo de la serpiente’s Academy Award nomination in the Best Foreign Language Film category has inevitably got people talking about the Colombian cinema industry. Journalists, critics, cinephiles – pretty much everyone seems to have an opinion.

Some applaud the film’s nomination and see it as a potential boost for the development of new cinematic projects in Colombia. Others, however, question the way distribution has been managed here, relegating national cinema and giving significantly greater exposure to more commercial Hollywood projects. What is true is that it’s a fashionable topic at the moment, and that can only be a good thing for the industry, as it has begun a discussion on its current state, as well as the efforts being made to give more support and exposure to national filmmakers.

As soon as the nomination was announced, the same old story began. Social media went into overdrive with patriotic messages of celebration, cinemas announced the re-screening of the film and praise poured out from the media – although it wasn’t purely based on its cinematic credentials.

It’s hard to tell whether this is just a momentary euphoria, another colombianada, after which we will just go back to movie listings inundated with commercial films, tasteless humour or made-to-order production.

El abrazo de la serpiente certainly has the credentials to justify being bathed in recognition, including impeccable production from Cristina Gallego, director Ciro Guerra’s wife.

If this movie is anything to go by, the production and storytelling in Colombian films are solid, so where is the national industry falling short? Film archivist and academic, Juana Suárez, explains: “The spotlight is on Colombian cinema now. This might be a good opportunity to improve the mechanisms of distribution and exhibition – the Achilles heel of the film industry across most of Latin America. Then we can see the work of more directors.”

Sandra Milena Ríos, member of the Círculo Bogotano de Críticos y Comentaristas de Cine.

It will be interesting to see whether El abrazo de la serpiente’s nomination will create the circumstances in which people will start to see national films as a viable entertainment option, so that these productions don’t continue to be confined to festivals or a couple of weeks on mainstream screens.

This historic moment – which will no doubt be considered a resounding success regardless of the outcome – is just the beginning of the road for the industry.

“The Oscar nomination doesn’t hide the shortfalls of the Ley de Cine, but without doubt it creates a good environment for continued investment in the industry”, explains Sandra Milena Ríos, director of movie blog Cinevista and member of the Círculo Bogotano de Críticos y Comentaristas de Cine.

She continues: “This is demonstrated by the recently-announced Proimágenes incentives and the launch of a free online distribution platform which includes four Latin American countries.”

The challenge for mass media and critics is to remember that, while we are talking about perhaps the most important recognition in the history of Colombian cinema – or at least the most high-profile – there are other films to highlight and plenty of successes to talk about. This last year, in particular, has been notable for outstanding productions such as La tierra y la sombra (Land and Shade), Gente de Bien or La ciénaga entre el mar y la tierra (Between Sea and Land), winner of the Audience Award and Special Jury Award in the World Cinema Dramatic category at the 2016 Sundance Festival.

El abrazo de la serpiente is nonetheless an inspiring story for Colombian cinema, as well as the entire Latin American industry. For Juan Martín Cueva, director of Ecuador’s Consejo Nacional de Cinematografía, it is important to take the lead of such films: “A visual and narrative production as impressive as [this film] fills us with satisfaction and hope, because it has been a hit not just with the critics and festivals, but with the public too.”

The story of the Colombian film industry is still in the making; hopefully it will offer more works of art from our creative and talented filmmakers. National producers have also been fundamental in the success that we are currently celebrating, with their impeccable and efficient work. The filmmakers and producers are doing their part, now the baton has been passed on to us: the moviegoers. And it’s up to us whether we let this current wave of excitement fizzle out or if we continue to support a burgeoning and talent-filled national industry.

The production crew on the set of El abrazo de la serpiente.

‘In the jungle everything has spikes’

Jazid Contreras spoke to art director Ramses Benjumea about the creative process behind this riveting cinematographic journey and the challenges of turning the wild jungle into El abrazo de la serpiente’s set

Bogotá Post: How did you get involved with this project?

Ramses: I’ve known Ciro since we were students at the Universidad Nacional. Our mutual friend, production designer Angélica Perea, told me she needed an art director that was able to understand Ciro and her, and we had already worked together on his second film, Los viajes del viento, in which I did the scenography.

Once I read the script my mind was blown. I thought ‘how can this be so well written? It’s so exciting and complex. I want to do this now’.

BP: El abrazo is known for its visual beauty. What was the creative process behind the art direction?

RB: This work started five years ago. We went through Theodor Koch-Grünberg’s journal, Two Years Among The Indians, as well as other books about the Orinoco region and the history of the Tukano, Bará and Tatuyo tribes. From there we configured a system of messages, a kind of graphic language.

There were important discussions on two topics. First, the black and white issue, and second, shooting in celluloid, using 35mm film. Both felt natural to create a flashback to the past. When I saw the finished movie I was struck by the sound mixing and how it played with the images. I feel like the colour is shown by the sound instead of the greens of the rainforest.

BP: What were some of the challenges of working in the jungle?

RB: Certain spaces demanded I work closely with the director of cinematography, because we had to recreate some grey scales that worked on film. Some of those spaces looked a bit ‘clownish’ to the naked eye, full of crazy colours, but they translated perfectly into black and white. None of us had made a black and white movie with such thoroughness.

Also, in the jungle everything has spikes, everything can cut you or poison you! But if you are patient, you find the charm in the undomesticated, you see life blooming all the time.

It was a very rewarding experience for everyone involved. Nilbio Torres, who plays the young Karamakate, had never seen a movie on a big screen, never been in a movie theatre and had never visited a big city. Suddenly, he began to travel a lot and understand what this whole movie magic is about.

BP: Where do you get inspiration as an art director?

RB: For this particular movie, I drew inspiration from movies like Twelve Years a Slave, The Mission and The Last of the Mohicans. But the movies that have left the biggest mark on me, in terms of art direction, are all of Stanley Kubrick’s films, especially The Shining and 2001: A Space Odyssey. I find their semiotic depth astonishing.

BP: That’s interesting, as the ending of El abrazo reminded me of 2001: A Space Odyssey. Was that intentional?

RB: Not really. There might be some similarities but that wasn’t intentional. The colour sequence at the end, after all that absence of colour throughout the rest of the film, brings you to a state of transformation that, eventually, is the one that Evan [one of the main characters] reaches. He is in a process of self-reflection and mutation, he is almost a jaguar, a payé or a shaman.

BP: Do any Colombian films strike you particularly in terms of art direction?

RB: La estrategia del caracol. The light, the colour and the forms recreate the misery and the poverty without being pornographic or scatological. I love that honesty and the impact it has on the viewer’s sensitivity.

BP: What was it like working with Ciro Guerra?

RB: Ciro has matured a lot. I think he’s quite brilliant and he is concerned for this country and wants to tell local stories by travelling the Colombian territory. The previous film focused on the northern coast, now this one goes down south.

BP: How do you see the future of Colombian cinema?

RB: With state policies promoting filmmaking and distribution, things like this will continue to happen. The 2003 Ley de Cine has ensured a constant stream of productions. This is an invitation for the new generations. It is important to go to places where the stories are waiting for us to tell them.

By Jazid Contreras

Winners of the Best Foreign Language Film category

The Oscars – a white-washed back-patting party or a glamorous homage to one of the world’s most popular art forms? The film industry’s most prestigious award creates a yearly buzz, not to mention the yearly polemic debates, but in spite of all the criticism the Academy Awards undoubtedly offer a chance for lesser known films, actors and directors to find new audiences.

Since the creation of the Best Foreign Language Film category in 1956, only a handful of Latin American movies have been nominated, with Argentina the only country to take home the statue – twice. So it’s not hard to understand the hype around the Colombian nomination for Abrazo de la serpiente (The Embrace of the Serpent).

This year’s controversy has focused on the lack of diversity among the acting nominees, certainly a valid point that highlights Hollywood’s struggle with modern realities amid equality concerns. However, the Oscars also give an opportunity to those films that might not otherwise have gained global recognition. Let’s face it, how many non-Spanish speakers worldwide would have watched a heavy black-and-white drama like Ciro Guerra’s film were it not for the golden statue nomination?

Here, we’ve handpicked some of the most memorable winners from across the decades:

Life Is Beautiful (Italy, 1999): Maybe one of the most memorable winners of all time, this film tells the story of a Jewish father and his son during the Holocaust. La vita è bella touches both heart and mind with a delicate balance between humour and drama.

Fanny and Alexander (Sweden, 1984): By some, regarded as Ingmar Bergman’s best, this is the story of two Swedish children and the tragedy of their family. It doesn’t get more Scandinavian than this.

The Secret in Their Eyes – Elevator Scene.

The Secret in Their Eyes (Argentina, 2010): Juan José Campanella’s winner revolves around a retired legal counsellor haunted by an unresolved homicide case and the unrequited love for his superior, who tells his story by writing a novel.

Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (Taiwan, 2001): An epic fantasy tale of a girl that gets her hands on a legendary sword with disastrous results. Ang Lee’s action drama did not only change the way people look at kung fu films but it also created a following and made way for a boom in the Asian film industry.

Journey of Hope (Switzerland, 1991): The theme of this film has once again become relevant due to the Syrian refugee crisis. Director Xavier Koller tells the moving true story of a poor Turkish family that tries to emigrate illegally to Switzerland.

Z (Algeria, 1970): This Algerian-French political thriller is based on Vassilis Vassilikos’ novel of the same name, telling the story of the assassination of Greek politician Grigoris Lambrakis in 1963. A dark but important film for its time.

By Daniel Ogalde