It’s a regular day in Bogotá, so I’m up and out early to take the dogs for a walk. The theme of disorder – and the part that small rules play in a functioning community – are on my mind. You don’t have to look far to see why. Whoever wins the mayoral race in November will be inheriting a city riven with little problems.

We have to be careful making our way across the grass, as a lot of owners don’t pick up their dogs’ shit. My dogs do their business. Once everything’s bagged up, I wander over to the nearest bin only to find it is filled up with rubbish and overflowing.

The dogs and I run up to the park. We dodge a motorbike that has decided to use the pavement as their own special carril. But then the way into the park is blocked. Buses and cars have ignored all the signs and lights, so we pedestrians can’t cross easily.

Into the park itself. It isn’t children we see in the playgrounds built for them, instead adults and dogs are exercising among the swings and slides. A mountain biker cuts across on the footpath, rather than use the trail provided precisely for him to use. Music blares from his speaker, then is gone as he hurtles down the hill.

An aggressive, off-leash and unmuzzled dog charges my dogs in fury, but luckily they’ve enough moxie to give it some back. I loop back towards home, reflecting on the fact that in a half hour of exercise I’ve seen a worrying number of low-level irritations.

It’s hard to ignore the fact that there’s a general lack of order at the moment in Bogotá. It’s far from being a broken city, but the cracks in society are as visible as the holes in the roads. It’s time to start working on fixing them before it gets any worse, because it’s not just serious crime in Bogotá that affects quality of life.

Why is it like this?

Most rolos are decent folk who follow not only the laws but also the rules for the most part. That’s a good thing, because strong societies are built on consideration for others – the city relies on people following their own moral compasses.

However, for those that do decide to flout the rules, there’s no real consequence. I speak from experience. I’ve called people out for both not picking up dog shit and littering. In my case, I was verbally abused and told to fuck off back to my country. A quick trawl through social media shows I’m not alone. The police simply turn a blind eye in most of these cases, either because of limited time and money or through sheer indifference.

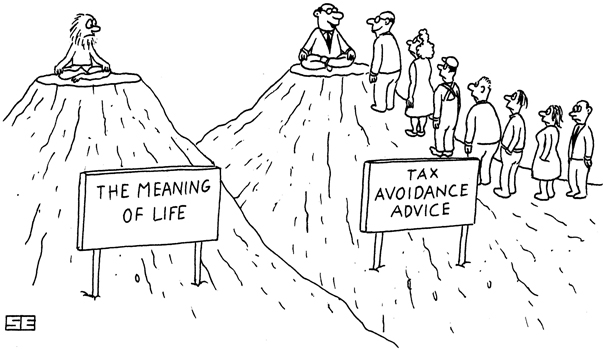

All the mayoral candidates are aware of this, but have different views on how to handle it. Lara and Molano both propose a mano dura, as with their plans on higher-level crime. The others mainly tend towards the ever-popular idea of education.

We’re suspicious of the education argument – there’s no one in the city that doesn’t know most of these things are wrong. The issue is that some people just don’t care and know they won’t be either called out or punished for doing them. Politicians love it though, because it’s cheap and visible.

A rubbish state of affairs

You can hardly walk far in the city without seeing enormous piles of rubbish. There are a number of aspects to this, from littering to fly-tipping to plastic overuse. There are seemingly no taboos to littering, so that’s the most common form that you’ll see on the streets.

For a start, many busy streets will be littered with mainly food detritus, from discarded bones and wrappers up to whole polystyrene trays. Cigarette butts are not seen as rubbish, so those will be strewn about, as will spat out chewing gum blobs. Often this will be in close proximity of litterbins, which may be overflowing.

This is compounded by an the attitude that people can simply use any given bin to throw away household waste. This is worryingly prevalent, with the primary offenders in my barrio being abuelas, who trot out to dump bags in the public bins despite the fact that we have rubbish collections every 48 hours. They just can’t wait a day.

On top of that, too, is flytipping, which seems standard for many building gangs. You’ll regularly see rubble piled up neatly in sacks at the corner of a park, but there’s also a good chance of finding furniture or white goods left out. Restaurants, too, often dump their waste into parks, so you’ll see hundreds of chicken boxes poured onto the streets.

The recicladores do an efficient job of managing recyclable resources. But a number of them simply rip bags apart on the street, meaning everything cascades out. This means that toilet paper and filthy food waste is lying about on the streets – the binmen can’t collect it but the stray dogs, pigeons and rats certainly will.

A number of people also use the city as an enormous toilet. This is partly understandable, as there are very few public toilets around. However, this means that people have nowhere to go if they’re caught short. For some, parks and streets as the only options. It should go without saying that no one wants to see human excrement in the city.

Of course, rubbish has long been an issue for Bogotá mayors, including now-president Gustavo Petro. Claudia López’ response has so far been to ignore the problem, it seems, which is how we’ve got to this point.

It’s concerning that the candidates aren’t making it a feature on the campaign trail so far, so it could well be sidelined again. For now, there is talk of change and greater efficiency and all the pretty words, while we all note that a decade on from Petro’s basura cero campaign in Bogotá, there is very much not zero rubbish.

Handling rubbish costs money. Bogotá has a comically high level of waste collection at three times a week, and that’s before you factor in the cost of sending out teams to clear up parks and do people’s work for them. Added to all that is the cost of vermin and so forth that are attracted to the rubbish.

Noise

There is a lot of ambient noise in Bogotá, from the constant buzz of motorbikes and vehicles to music being played loudly and anywhere to dogs that yap constantly. To a degree of course, this can’t be avoided in a big city. And Bogotá is certainly better than many other large cities in the country.

Although vehicle users often complain about the regulations they must pass to keep their vehicle on the road, there seems to be little attempt to monitor them for noise output. Motorbikes are the biggest culprits here, with whining engines seemingly a standard. Combined with a propensity to sound horns at anything and everything, this makes roads very loud to be around.

Sure, certain areas of the city are well-known party zones. No one can expect to live close to Galerías and not have a lot of loud clubs banging out tunes. However, there’s a trend towards parties taking place in more residential neighbourhoods, which irritates some people.

It’s also worth noting that Bogotá doesn’t really have commercial zones, so there is always nearby housing. Candidate Juan Daniel Oviedo is the most associated with nightlife, cheerfully championing bars such as Asilo. It’s widely thought he might try to expand the number of areas that have permission to party until 5am.

There is a growing debate over what to do with nightlife. The extension of party hours to 5am in certain areas has reinvigorated the night economy, splitting opinions. Some feel that expanding the number of party zones will lead to increased noise pollution and associated drug/alcohol related disorder. Others see the opportunity for more employment, freedom and profits.

There’s also an absolutely bizarre obsession of the local government with carrying out building work in the wee hours. This is to avoid traffic congestion within peak hours, but it means that anyone living nearby has to put up with the sound of steamrollers flattening tarmac at 3am.

Vehicular menaces

At times Bogotá feels like a city for cars, not people, as cars regularly park wherever they like, whenever they like. Sometimes that means they’re on the pavements, which blocks the path for pedestrians trying to get around their city. At other times, they park on the streets themselves, delaying traffic and obstructing bus lanes and so on.

This affects all of us, but particularly creates problems for less-able pedestrians, such as the elderly or people using wheelchairs. With cars growing ever-bigger year-on-year, the already poor state of walkability in Bogotá gets to be even more of a hassle. It’s not easy for everyone to walk around a 4×4 on a pavement or to climb a kerb if a ramp is blocked.

Sometimes, cars will even barge over rumble strips and park in (supposedly) separated bike lanes. On that last point, they’re far from alone. Bike lanes often seem to be defined as simply not-car lanes, meaning you’ll find reciclador carts, motorbikes, runners, walkers and mopeds that self-identify as bicycles.

The last of those, the motorised bicycles so beloved of rappitenderos are a particular irritation. These machines use 2-stroke engines stuck onto a regular bike frame in order to power the drivetrain. Of course, these machines are basically unregulated, uncontrolled and uninsured despite essentially being mopeds. The same is true of the electric scooters growing in popularity.

In general, traffic signalling is ignored, creating more traffic and therefore more pollution and noise. Because so many cars and buses jump red lights, it’s very common that pedestrians are stopped or inconvenienced when the zebras are blocked. For the less mobile walkers among us, that can mean being unable to cross.

Animals

Colombia is generally a nation of animal lovers. This can sometimes cross the line, and nowhere is this more visible than with pet dogs. Dog shit is the obvious one, with a significant number of owners not taking responsibility for this and therefore most parks and many streets are covered in dog turds.

Many dogs wander about offleash, even within heavily built up areas. This isn’t great for the dogs themselves, as they can and do get hit by cars. There are other concerns though, as many people are afraid of dogs and shouldn’t have to live in fear. Given the predisposition towards large aggressive breeds, this isn’t unfounded. Dog attacks are a lot more common than many think in Bogotá, with over 50 daily.

As many people use dog walkers, you’ll often see unscrupulous dog walkers, overloaded with four-legged charges, which is fraught with danger. Others, meanwhile, simply chain the army of dogs to a fence and wander off, in the broad light of day.

Strays, too, are an ongoing problem, with an enormous population that no one wants to take action on, as it will incur a lot of wrath. In fact, people merrily put out food for stray animals or pigeons, which inevitably gets nabbed by rats and mice, perpetuating vermin problems and occasional population collapses and the inevitable corpses.

Animal abuse is also common, especially at lower levels. Quite a few people will punish dogs by hitting them, with some even carrying sticks specifically for this. Others leave animals alone, often outside on patios or terraces, where they howl for hours on end. This in turn can lead to neighbours throwing poison for the dog to eat.

Public space

The misuse of public space is endemic within Colombia, with many people seeing public areas as their own personal playgrounds. As seen in my daily walk, quite literally in the case of adults and animals misusing children’s spaces.

It’s not fair to any children who are allergic to dogs, and neither is it fair to the dog not to be able to really run. Worst of all, if this space is blocked off, the kids can’t actually enter to use the facilities made for them.

More broadly, the equipment isn’t designed for such large people and gets damaged. And that’s the issue with a lot of the misuse of public spaces. Not only does it rob us all of the ability to enjoy our shared spaces, the damage done also means our taxes have to be spent on repairs.

For example, the topographic map of Bogotá and the surrounding area in the parque nacional was recently repainted. It is already damaged from people hopping the fence to clamber all over it.

In parks, you will frequently see people hosting private parties in a public space, or simply erecting tents for themselves. This colonising view of empty land ruins the view for everyone else, before we get into the associated litter and noise pollution. Who wants to listen to the wonderful birdlife of Bogotá, anyway?

There’s a cost to allowing street hawkers to operate with impunity too. It’s one thing to have an empanada seller in a residential district, but right next to an actual empanada stand is just taking the piss. This hastens the decline of smaller shops and independent operators, who don’t have the resources to get the police to step in, whereas the larger chains are more able to get attention.

Not just an old man shouting at clouds

While these issues may seem fairly minor in the grand scheme of life in a thriving metropolis, they all lessen our collective quality of life, which is problematic. Worse still, they lead to a general belief that the city isn’t functioning, which means there’s less incentive to pull your weight, creating a vicious circle.

Worse yet, the more signs of disorder that you see around the city, the harder it is to build and foster a sense of civic pride. Combined with that is a growing sense that you can mug off the laws and rules that knit us together as a society. Once we do that, it becomes easier to ignore other rules and creates a more divided, selfish city.

In this article, we’ve tried to talk only about things that are breaking societal laws and affecting others. Crime for was covered in our previous article on crime in Bogotá, and before that the transport issues. We also tried to choose things that we think genuinely irritate a number of people.

Some of these issues are on an upward curve, others downwards. Rubbish has definitely got worse in the last few years, but there’s a growing number of dog owners acting more responsibly in terms of leash laws.

So what can be done going forward? We’d like to see the new mayor of Bogotá bring in more enforcement of basic rules. That could be as little as taking someone to one side and having a word to nip something in the bud before things get worse.

These problems mainly stem from people being inconsiderate berks, not evil people. This means that there’s plenty of chance to change with some judicious enforcement from authorities when needed and from fellow citizens at other times. After all, most people agree that these things are wrong.

It would be nice to build a society in which there were more taboos around things like littering to dissuade people from doing them. It would also be nice not to be called a sapo for asking people to use a litterbin. Perhaps that’s a way off, but we’d like to dream.