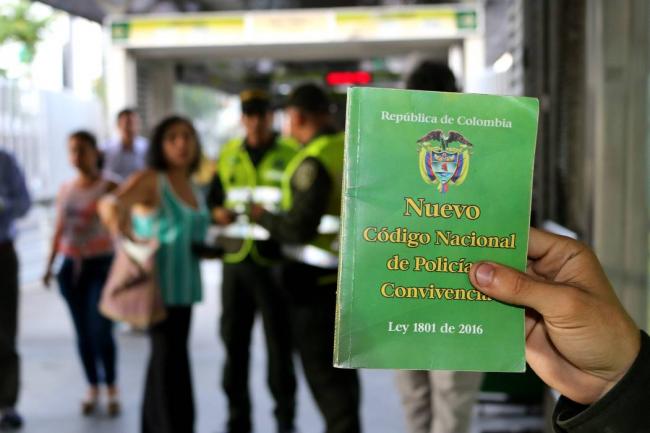

The new Police Code has come into effect and is dividing opinion as to whether the new laws are making things better or worse.

On January 30 this year, the new Police Code came into effect. The legislation is meant to increase enforcement for lower level offences, and contribute to a more peaceful co-existence for citizens. Made up of over 240 articles, the code covers everything from fines for acts of vandalism to cracking down on the sale of previously stolen goods. Until July 30, the controversial code will largely be in trial mode, with a focus on adequately training police officers and only issuing smaller fines – the full amounts will be applied after July. Despite this, in February alone the police applied over 100,000 fines – and, for better or worse, citizens have started to notice the effects of the code.

Laura Sharkey asked for people’s thoughts about the new code – finding a divide between those who see it as a well-overdue solution to the city’s security problems and those who believe it unnecessarily infringes on basic rights.

Many people support the implementation of new fines.

In favour of fines

Many argue that the new Police Code was not only a long time coming, but is also a step in the right direction for Colombia’s development. According to Sergio Guzmán, a Colombian analyst who specialises in security matters: “The new Police Code, as opposed to the old way of doing things, represents exactly the kind of society we want to live in. We don’t currently live in a mutually respectful society so we need rules [and] a Police Code which cajoles us into revamping our citizen culture – it’s the carrot and stick theory at work here.” Furthermore, according to Guzmán, “an update of the Police Code means that the police have clear operating procedures. This, in turn, gives them the tools to fight crime.”

Jaime González, a Bogotá accountant, agrees. “The best thing about the new Police Code,” he says, is that, “the police will have to do a job which they have never done before – that is to avoid conflict instead of simply reacting to it. Now they don’t have to wait until there is a security emergency to do their jobs. For example, the biggest public order problem we have in Colombia is noise, and you will often find four or five people listening to music at full volume, who make life a misery for the whole block. Now, the police can intervene before this becomes a broader cohabitation issue, or worse, a casualty.” In this respect, for González, while some of the articles of the code may be a little extreme, they are necessary to educate citizens about coexistence.

Then there are the individual experiences. One of the articles of the Police Code prohibits street vendors. According to Ana Espitia, an international relations graduate from Valledupar, the results are already making people feel safer. “I must admit – some of my friends are happy that the street sellers outside their houses are no longer there. It is no longer uncomfortable for them when they are coming home late, where they used to feel insecure. There are a lot of people who see this as a positive thing because these people did not pay taxes for their stands [but] this isn’t my personal view.”

Juan López, a Bogotá resident, says “I must admit I have seen a difference, but mainly when it comes to public scandals and order. I think that people now think twice before making a scene. Certainly, you see this in some of the poorer neighbourhoods where this was an issue before. Also, the main thing I have noticed is the TransMilenio – the people who cut the line – you don’t see this as much anymore. That has to be a good thing right?”

There are many who think the new Police Code is repressive.

Against the code

The ones who seem to be most against the Police Code are, perhaps logically, those who are most affected by it. Álvaro, a local informal fruit seller, says that within the first two months of the Police Code he was fined four times as part of the crackdown on informal commerce. The fines have since stopped after extensive protests from the thousands of vendors who rely on their incomes to feed their families. According to Álvaro, “the government changed its priority and now is less focused on these people, but that doesn’t stop the fear.”

Mari Luz, a domestic worker, agrees: “My sons used to work as informal street sellers and this was a fixed income for them. They weren’t involved in anything untoward. But now that this is too difficult, I worry. If there isn’t that income security what will these thousands of people do? Surely it will encourage them to turn to crime.” If this is true, then there is the possibility that the Police Code will have the opposite effect intended and crime levels could go up in the short term.

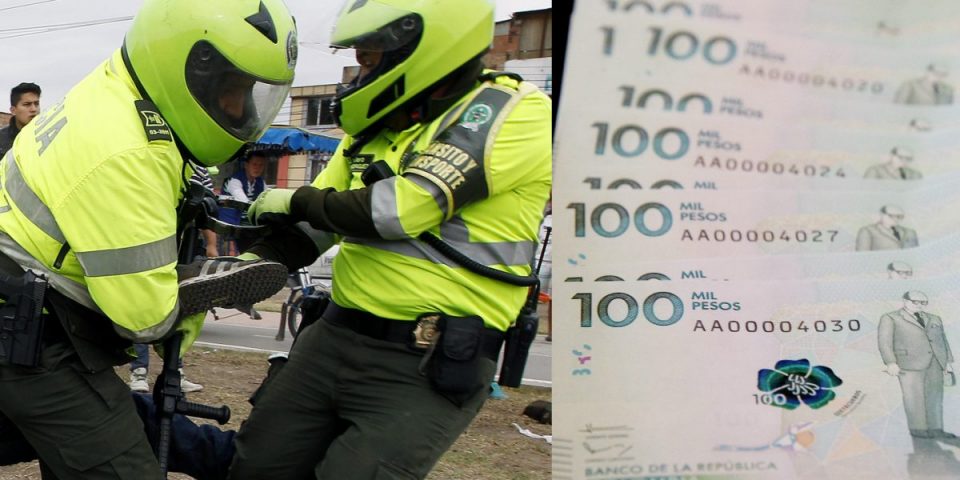

Guzmán doesn’t focus on this particular point, but does add, “the negative thing about the code is that it didn’t have a trial period so there has been a lot of friction with its implementation precisely because those who developed it didn’t think about the implications it would have for many people. It will take time for an adjustment to be made. It was made from a security-based not human rights-based mentality – which is at complete odds with what the job of the police is.” For example, he says, “Entering homes without a warrant is bad from a civil liberty standpoint – the police are using judgment to enforce the code. Many will be right, but many will be wrong. There will be many cases involving police abuse.”

Guzmán is not the only one to think this – many are worried about the potential for corruption from police officers, now that they have more arrest powers than previously. More than three people told me that they were worried about the police having so many rights. Juan López stated, “The fact that police can enter a house without a warrant worries me, and I know that there are a lot of organisations worried about the same thing. This puts so much power in the hands of the police, which is a notoriously corrupt institution.”

With the new police code being implemented since January, some people say that the difference is minimal.

However, for many, the changes since the implementation of the Code are simply too minimal to note. This was the most common reaction – that it is far too early to tell what the impact is, especially given that full fines will not enter into effect for a number of months. Diego Benavides, political science graduate from Bogotá said, “I know there are some changes but I am not aware of [them]. All I have to go off is what my friends say, which is that the police just do the same as they always did – for example, you call the police and ask them to help turn down the music, but now they just do the same as before. They tell you to turn the music down and that’s it. There is no change.” In this case, it is a waiting game and only time will tell the full effects of the code.

A similar issue, and perhaps the most worrying, is that many people simply do not know what is in the code. Diego continues, “I’ll be honest – I haven’t read the code and I genuinely haven’t noticed any difference. The only parts I have paid attention to are those which affect me – I ride a bike so I know the things about bikes, but that is it.” He commented, “The government has not divulged enough information to know what it is about. I mean, how can you expect the average Colombian to understand it?” Benevides is right, and this is likely going to be the biggest obstacle for the code. People will not be aware of how much it contains until unfortunately, they are faced with the law, and potentially a hefty fine, and are then forced to know what it is all about.