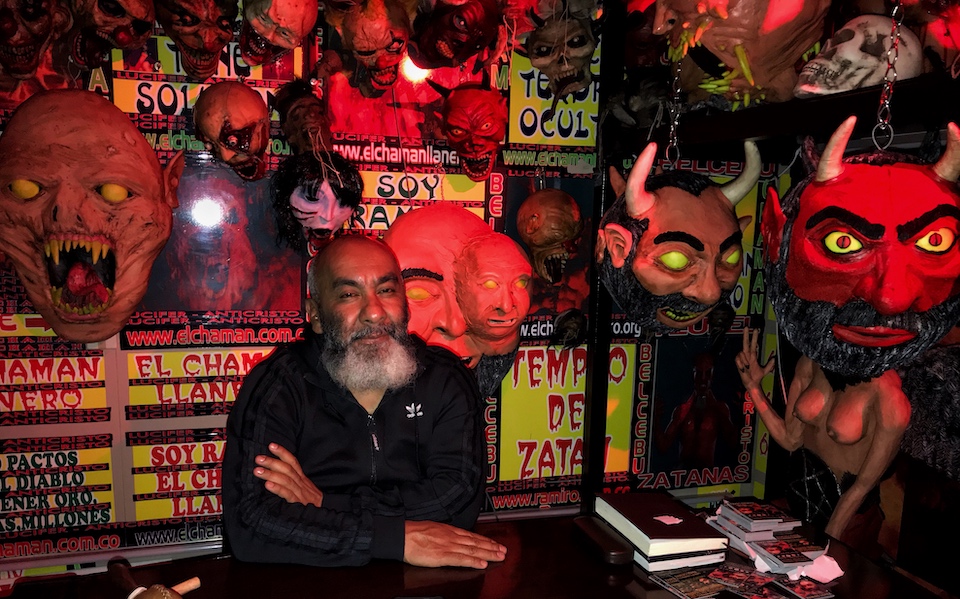

Image by Jonathan Hernández.

Last week Gustavo Petro tweeted that the followers of former president Alvaro Uribe “rape journalists and murder witnesses. And yet, there are people who believe that they are a political alternative that deserves to govern Colombia.”

Some things never change. Gustavo Petro is likely to play out his role as antagonist to that strain of politics within Colombia called uribismo till his last breath. Petro originally played thorn in the side of President Álvaro Uribe himself as his biggest critic from the parliamentary pulpit from 2002 to 2006.

Now, rather than attack Uribe, his focus has shifted to the new standard bearer of uribismo, the former lawyer Iván Duque of the Centro Democrático party. At this stage, Petro is unlikely to win an outright majority at the end of May and he will probably face off Duque in the final round in June. What are his chances of winning the presidency?

***

Fiery, firebrand and fired up, Petro could fill stadiums with his followers. He could probably fill stadiums with his detractors too. His rockstar appeal landed him on the cover of Rolling Stone, which accompanied an article in which he spoke of how his time in prisons around the country and his torture at the hands of the military allowed him to see what the workers of the country had to endure. Having joined former rebel group M-19 as a 17-year-old, Petro carried out often violent acts against a state that he felt was corrupt to its core and worthy of overthrowing. The group disarmed in 1990 and Petro was brought into the political mainstream.

Yet he never shook off his formative revolutionary roots and, in 2018, political molotov cocktails like Petro are all the rage. Earlier this year, El Pais columnist opined that “the new popularity of Petro is a sign of a populace bored with traditional leadership. An excess of corruption, incompetence, bad administrations, unfulfilled promises, injustices and inequalities etc., have led people to dare to make a different bet.”

Despite his popularity however, his main problem come June may be the one that galvanised his support for him in the first place: his unwillingness to budge on principles to appeal to more centrist voters. As his debate performances have suggested, he is unlikely to ever be the statesman that the current Colombian President Juan Manual Santos is. Smug and at times overly professorial in his explanations, Petro has been unwilling to unify a fractured electorate in favour of lecturing on his vision.

Another major challenge that Petro faces is to disabuse the many voters in this country that he will turn Colombia into another Venezuela. Although Petro has praised Venezuelan strongman Hugo Chavez, he has since sought to distance himself from the Chavez model of governance. One crucial aspect in which he differs from chavisma is his desire to move the economy away from a dependence on fossil fuels and onto a model that favours agriculture and renewable energies.

Perhaps in an attempt to persuade those who still give him the moniker ‘Petrosky’, at the fourth debate, he singled out New Zealand as a possible model that Colombia could follow rather than other failed models of socialist governments.

Despite little mention of Hugo Chavez on the campaign trail however, some foreign investors have already voiced their likelihood of leaving the country with their money should he win and many remain concerned that he will make markets nervous.

A third major concern that Petro faces is whether he will be likely, as President, to follow through with his drastic reforms. On the issue of health, Petro intends to centralise public health by way of a government body (like that of the NHS in the UK) that would overlook the services provided by public health institutions. He would also attempt to control the price of drugs by renegotiating free trade agreements with economic allies.

With respect to education, Petro is also aiming to upend the paradigm in favour of the working poor so as to ensure that they too have an opportunity to escape poverty. He intends to insure free and universal education from the age of 3, regardless of a child’s background. Priority is also given to rural children to ensure that their distance to urban centres doesn’t disadvantage them. The improvement of science and tech education is also a crucial pin in his desire to move away from fossil fuels and towards combating climate change.

And finally, his views on security and crime, which are at starkest odds with Germán Vargas Lleras of Cambio Radical, focus on a prevention and rehabilitation model over a higher incarceration approach that the former Vice President favours. Petro specifically referred to the high rates of juvenile incarceration as being unacceptable during the first debate.

Gustavo Petro will need to convince the electorate that he can commit to enforcing his grand plans if he were to be in office.

The people of Bogotá are likely to be the most sceptical of whether he can do so. As mayor of the capital he had his share of praise and criticism though he did leave office with very low popularity ratings–over 70% disapproving of his tenure. “At the end [of his mayoral tenure], there was the feeling that Petro was very good at denouncing the corrupt, but very bad at managing public resources,” columnist Óscar Montes wrote for El Heraldo, “‘We lost a good congressman and won a lousy mayor’, was one of the phrases most heard during his administration.”

Which is perhaps why it is so surprising that he has come this far and on the cusp of a duel with Ivàn Duque for the chance to occupy La Casa de Nariño– Colombia’s equivalent of The White House.

***

Even his supporters who want to see him win are surprised to see him come this far and believe that forces beyond Petro will ensure that he won’t get further. Electoral irregularities and voter intimidation are common tactics used in Colombian politics to sway elections and Petro has already been the target of an attack when, before a campaign event in Cúcuta, his car was pelted with stones.

May has begun and it is the first home stretch for the candidates. By the end of it, Petro will be hoping that the next chapter of his compelling story will be as President of the Republic. His chances lie on whether he can convince Colombians he isn’t as scary as his opponents make him to be and the likelihood he can make good on his more ambitious promises.