Armed gangs lurk in the shadows of Santa Marta taking money from local businesses and, in some cases, attacking them.

It is hard to imagine that armed groups still exert control in the tourist haven of the Sierra Nevada. But while visitors flock to the region to enjoy Parque Tayrona’s jungle-backed beaches, and the lush landscapes of Minca, a darker reality lies under the surface.

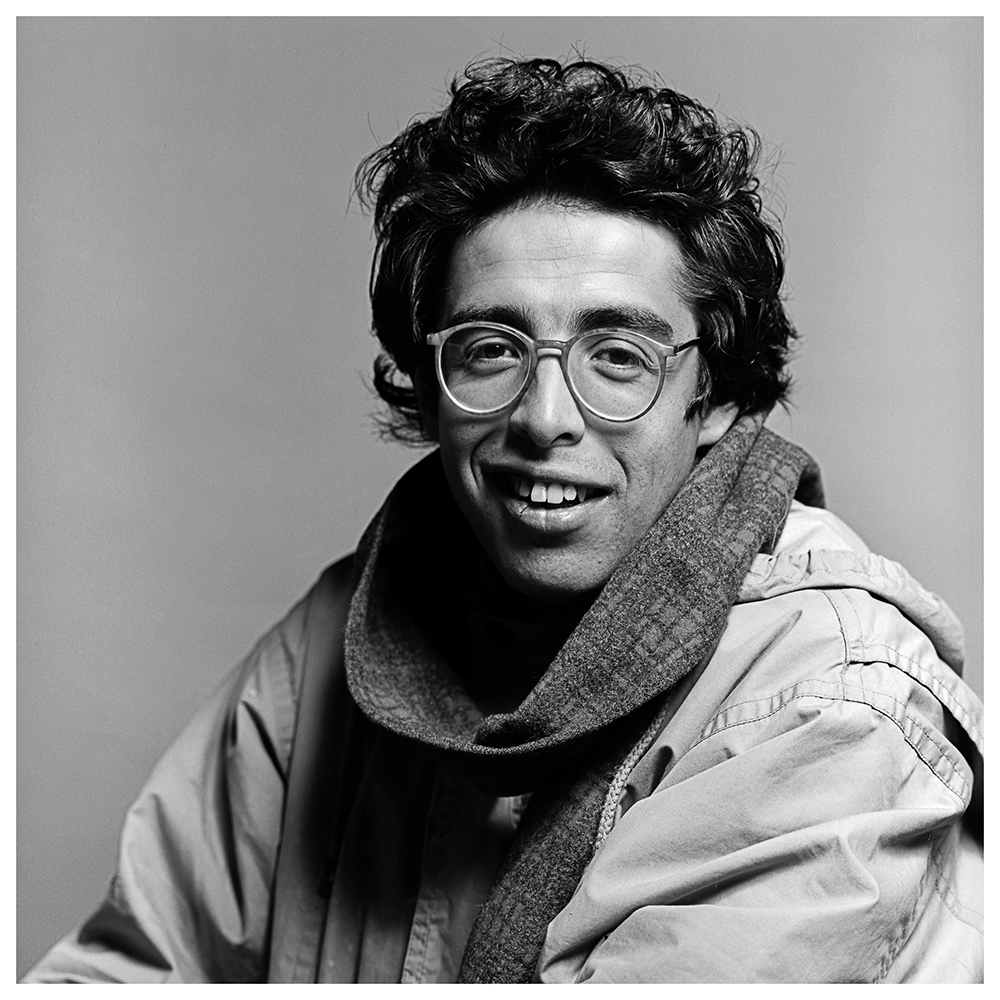

Following last edition’s interview with a British settler whose nature reserve in Minca had come under threat from armed groups, we spoke to Patrick Fleming, originally from Dublin, who had also suffered at the hands of Los Pachencas.

Fleming’s idyllic farm, Paso del Mango, and the life he had built there, came to an abrupt end in April last year when armed thugs burned his property to the ground. “Within a couple of hours the place was just destroyed, it’s like a bomb hit it, there was nothing left inside,” he said, “I was distraught, completely distraught, because I felt like part of the community, I thought, how could this happen?”

Before

After

Fortunately, Fleming and his wife were not at the farm the evening of the fire. Witnesses described how a group of men, with their faces covered, came with gasoline. Fleming noted that the timing was “suspicious”, given that he was planning on going the following day to take photographs of the new holiday homes.

Unfortunately, these stories are by no means unusual. Since 2017, attacks of this kind have been on the rise in the region. Fleming said that similar things have happened in Palomino and Minca, but until recently did not get much coverage in the media.

Back in 2001, Fleming bought a piece of land up in the mountains of the Sierra Nevada, just outside of Santa Marta. He was later to realise that this territory was under the control of Hernán Giraldo, also known as ‘Lord of the Sierra.’ The paramilitary leader, who is now in prison in the US, had tight connections to the state security apparatus.

Great expectations

However, after the demobilisation of the Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia (AUC) in 2006, Fleming says that things settled down and a “sense of normality” returned to the region. He planted mango and avocado trees on the farm and built two houses, with the intention of renting them as holiday homes. Sadly, that plan was never realised. He commented, “There were great expectations, I had great expectations that Colombia had turned a corner. But it doesn’t seem to be the case.”

Known in Colombia as a ‘GAO’, Grupo Armado Organisado, Los Pachencas are involved in drug trafficking, fuel smuggling, extortion, kidnappings and assassinations. The gang are thought to have formed in 2007 after the demobilisation of the AUC.

Today it is the cocaine trade that is at the heart of the problem. The National Police held the gang’s leader responsible for controlling 80% of the narco-trafficking routes along Colombia’s northern coast, from La Guajira up to the Magdalena department.

As we reported last month, the situation started to shift in early 2019 when Los Pachencas killed over a dozen people in the Santa Marta area and were suddenly in the news. Colombia’s political leaders declared the bandit group’s leader, alias Chucho Mercancía, a priority target: he was killed in a shoot-out with national police special forces last month.

Before

After

Many hope that the demise of Mercancía will bring an end to the terror that lurks in the shadows of the popular tourist destination. But Fleming – along with many commentators – is not optimistic. Even if their leader is dead, there are other gang members ready to take his place, and indeed other criminal groups waiting in the wings.

“That’s because there’s too much money to be made. It’s just a huge amount of money that greases a lot of palms, right up to the top. So as long as that trade continues you will have one group or another vying for control,” explained Fleming.

Conflict-analysis website InSight Crime agrees, recently writing that the Los Pachencas group has “weathered massive drug seizures and numerous captures in the past, thanks to its ability to renew its criminal networks.”

Perhaps to prove this point, in June the gang used death threats to enforce a three-day shut-down of commercial enterprises in the Santa Marta area, as part of their mourning for their slain leader. Anyone disobeying would become a ‘military objective’. Despite army and police reassurances, most businesses stayed shut.

La Vacuna, no vaccine against violence

Against this background of constant violence and demands, many local property and business owners prefer to pay vacunas – literally meaning vaccines – or protection money to the armed groups. Even part of the fee that travellers pay for the Lost City trek has ended up in the pockets of Los Pachencas.

It is hard to know how many people are actually paying the protection vacunas. Fleming said, “I know a lot of people are paying vacunas in the area […] A lot of people won’t admit it because it is actually breaking the law.”

Related: In the shadow of Los Pachencas

Fleming was always prepared to leave the zone if he had to, rather than give any money to these groups. He explained, “What you’re doing is actually supporting them and buying their bullets and their arms. And so you are in some way responsible for the next killing committed by them. But you have to live with your conscience as well – you can’t have a good night’s sleep thinking about the money you are paying these thugs.”

As prepared as he was to leave rather than give in, the fire came as a shock because he had not been threatened or asked to pay anything beforehand. He considers that perhaps it was some kind of warning to the wider community, to pay or face the same consequences. “It’s about controlling an area, when you have a community that is paying protection money you control the area and people will be afraid to speak out about what dodgy activities might be going on,” he said. “The vacunas for them are small change. Behind this, it’s really about the cocaine routes.”

As for Patrick Fleming, 18 years after his ‘Colombian adventure’ began, he has embraced the quiet life. When asked how one goes about moving on from such a destructive event, he says that he looks to Buddhist practice for guidance. “One of the main teachings of Buddhism is impermanence, everything is impermanent – which certainly proved the case in April last year.”

He has now moved to a sleepy rural pueblito that couldn’t feel further away from the heat and the danger he faced in Santa Marta. Fleming seems at peace with his new life, but he misses the farm up in the mountains, and the future he had just finished building.

The case remains ongoing; at the moment 12 people have been arrested in connection to the fire and general extortion in the area. As Fleming continues to search for the truth, the rest of the community he had to leave behind are left waiting to see whether the cycle will repeat itself once again.