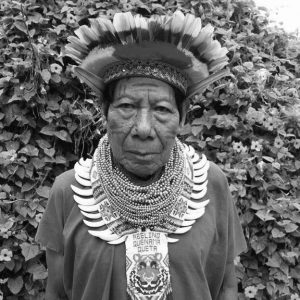

My first glimpse of Abuelo Avelino, an 85 year old Taita (Healer) from the Cofan tribe in Putamayo, comes early on in the night as I am setting up my place in the palm-thatched ceremony hut, known as a Maloka. I am here for a very special ceremony of Yagé (pronounced Yah-Hey), the Colombian name for the more commonly known Ayahuasca, a hallucinogenic plant medicine made from a thick, woody vine found only in the Amazonian Jungle. The difference in name lies in the way the brew is prepared – whilst both variants use the exact same type of vine (Banisteriopsis caapi), Ayahuasca is mixed with the leaves of the Chacruna plant whereas Yagé is combined with Chagropanga leaves. The woody stems and bark of the vine act as monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibitors which when combined with the Dimethyltryptamine (DMT) found in the added plant leaves can elicit a potent and intense psychedelic experience

Although Colombia’s indigenous Amazonian tribes have – like their Peruvian, Brazilian and Ecuadorian counterparts – been ritually using Yagé for millennia, travel by foreign spiritual seekers for the express purpose of taking part in ceremonies is a relatively new phenomenon in the country. The concept of ‘Mystical Tourism’ has been well established in Peru for decades but has only in recent years taken hold in Colombia. According to one leading Ayahuasca retreat review site, Ayaadvisors.org, there are currently 5 Colombian retreats listed compared to 6 in Ecuador and 28 in Peru.

I had first heard of Abuelo Avelino from my usual Taita, Greison Leonidas Lezama during my time at Eagle Condor Alliance, an organization that runs Yagé retreats in Santa Elena, high up in the mountains surrounding Medellin. Greison had trained under Abuelo Avelino as an apprentice Taita in his jungle homeland and could not speak highly enough of his teacher’s ceremonies. “The Abuelo only ventures out of Putamayo to Medellin once a year to hold a special ceremony, an honor that should not be missed” says Greison. Affectionately known as the ‘Jungle Yoda’, the elderly Taita sits together with Greison by the low smoldering fire, focusing on the ceremony ahead. Both are quiet and somber, faces obscured by the darkness, smoking thick cigars and sending wispy plumes of blue-tinged smoke up to the palm thatching above. Tobacco is one of the seven sacred medicines of the Americas and its use in Yagé ceremonies is abundant and encouraged.

A common deterrent that I hear from friends apprehensive about taking Yagé is that they fear they will lose their minds, or even worse, die. Widespread international media coverage about deaths during Yagé ceremonies have helped to disseminate the commonly held perception of the risk and danger when ingesting the plant. With ominous nicknames such as ‘Vine of the Soul and ‘Vine of the Dead’, it is no wonder that the plant has a certain reputation.

However, It is clear that not everybody reads into the negative hype surrounding Yagé as the Maloka begins to fill with ceremonial participants seeking anything from spiritual growth, answers to lifelong existential questions, confrontation of childhood trauma to simply quelling curiosity. As the numbers swell to capacity, the inside of the ceremony hut resembles an evacuation center with people on straw mattresses lining the entire length of the wooden octagonal walls and crammed around the large fire pit at its center.

However, It is clear that not everybody reads into the negative hype surrounding Yagé as the Maloka begins to fill with ceremonial participants seeking anything from spiritual growth, answers to lifelong existential questions, confrontation of childhood trauma to simply quelling curiosity. As the numbers swell to capacity, the inside of the ceremony hut resembles an evacuation center with people on straw mattresses lining the entire length of the wooden octagonal walls and crammed around the large fire pit at its center.

A very interesting assortment of people attend Yagé ceremonies. From dreadlocked spiritual seekers to white collar professionals to groups of mullet-topped teenage Colombians, they range the full spectrum. This evening, I talk to a lady named Gloria who runs a television program on TV Agro in Medellin. She tells me she has been running the same program for over 10 years now and is hoping the ceremony will give her some inspiration to update it. I also meet a lady named Maria Fernanda in her mid-30s who has two young children and a husband that passed away suddenly the year before. She is now a single mother and hopes the ceremony will help her find some meaning from her difficult experience.

As the time to ceremony draws near, the abuelo positions himself behind the front counter of the Maloka, a makeshift jungle bar made of wooden planks. This is where the Yagé is to be delivered to participants in a small wooden goblet. Abuelo Avelino continues his preparation as the younger Taita Greison delivers an introduction to the rules, expectations, and importance of the special ceremony with his elderly teacher. The 45 plus participants crammed into the Maloka listen intently to the young healer as their faces are illuminated by the flickering light of the now fiercely burning fire in the center of the room. Their ages range from literally a months old baby (whose parents place a small dab of Yagé on its tongue) up to a 70 year old woman who is seeking spiritual guidance during her battle with cancer. An atmosphere of anticipation, optimism and apprehension engulfs the Maloka.

After Greison’s introduction, the ceremony starts with the call for men who have never taken medicine before to approach the counter, they would be the first to drink. To my surprise, there is a young boy amongst these men, a child of perhaps 8-10 years old. This was the first time I had seen a child take the medicine and I wasn’t quite sure how I felt about it. The 8 men and a child take the cup and soon enough it’s the call for men who have taken medicine before to come up. I go to the back of the line and try to ignore my apprehension at the unpleasant taste of Yagé. As I approach the counter, I see the Abuelo for the first time up close. His 85 years fit snuggly into a petite 5 foot 3 frame – with kind eyes and a warm smile framing his wise, weather-beaten face. I take in his blue tribal shirt, parrot-feathered headdress and the large boar tooth necklace around his neck as he hands the wooden goblet over the counter to me whilst chanting incantations.

I take the thick, bitter brown liquid to my lips. It has the consistency of a thick custard but does not taste anything like it. I struggle to get it down and desperately take the cup of water Greison hands me to clean out the taste and wash down the rest of the Yagé. I manage to get it all down and go back to my straw mattress to lie on my side and meditate.

Before the ceremony, I learn from Greison that it is seen as an honor for Taitas to keep the Yagé in and not to – as the action is politely referred to in Colombian Spanish – Aliviar. Focused on this new idea, I am intent on not purging during the ceremony even though I have purged every time I have taken Yagé previously. I knew it was going to be a challenge but I was determined.

After taking the goblet of Yagé, I feel quite relaxed and remarkably unaffected compared to what was going on with the other participants. There is nothing quite like the cacophony of noises and theatre of confronting sights that one experiences during a Yagé ceremony. Tonight’s action begins almost immediately from all corners of the Maloka even though personally I still don’t feel anything. I am focusing on my own process but it is hard to tune out my surroundings. Apart from the loud vomiting, sighing and dry heaving noises, there is a young guy outside screaming at the top of his lungs continuously “Dolor, Amor, Se siente” (Pain, Love, Feel it) and a large shirtless, bald man rolling around on the floor next to the fire and stomping his feet loudly on the wood with noisy thuds. Abuelo Avelino and Greison play harmonica and chant to calm the energy, sometimes in unison and sometimes solo. As taitas, they also take medicine during ceremonies and their chanting comes directly from what they feel of the medicine. Their chanting seems impromptu and otherworldly but it works and the intensity of the ceremony settles down.

After about two hours, I finally start to feel the Yagé.

It starts with the feeling of mariado, a mixture of dizzy, weak and uncoordinated. The queasiness starts too but I do a pretty good job of breathing into and suppressing it. This works well for a while and I begin to think that I am going to accomplish the goal of not purging like Greison had suggested. However, it is at this time that I have my ‘limpieza’ (cleansing) with Abuelo Avelino – a process that involves each participant sitting on a small wooden stool with their bare back facing the Taita. He then uses a bunch of dry branches known as a wayra to ‘cleanse and heal your energy’ whilst chanting incantations. Up until this point, I felt I had the nausea quite under control but the cleansing was like pouring gasoline on a fire.

I made it out the door just in time. So much for not purging.

Whilst outside, I feel the full force of the Yagé as I try to hold back the gut-wrenching nausea. Heavily under the influence, I think about asking the plant about the future but I am overwhelmed with a clear, strong thought that I don’t want to know the future. I’m perfectly content enjoying the ride. I remain outside with this nausea and mental dialogue for what seems like hours. As the nausea slowly subsides I go back inside in the search for warmth and bury myself in my sleeping bag. Eventually I warm up and the effects of the medicine wear off. It’s been a long night. I had no idea what to expect on this special ceremony night with Abuelo Avelino: the Jungle Yoda. It ended up being a very intense experience, both physically and mentally. Although I didn’t receive any specific instruction from the plant, I did come out of it with a general feeling of satisfaction, well-being and knowledge gained from keeping a positive and appreciative mindset throughout the ceremony.

There is no way to guarantee what type of experience each person will have with Yagé. People take part in ceremonies for a multitude of different reasons and no two people’s experience will be exactly the same. An equivalent dose of the exact same brew of Yagé can illicit polar opposite effects on different people. At the same time that one person could be going through a very difficult, physical struggle another could be having a beautiful, dreamy experience. They say that “Mother Ayahuasca will give you want you need, not what you want.” I can’t speak for anyone else, but my personal journey with Yagé has definitely benefited my life on a mental, emotional and spiritual level.

For those interested in trying Yagé, the Eagle Condor Alliance runs 10 day retreats as well as monthly community ceremonies in Santa Elena, just outside of Medellin.